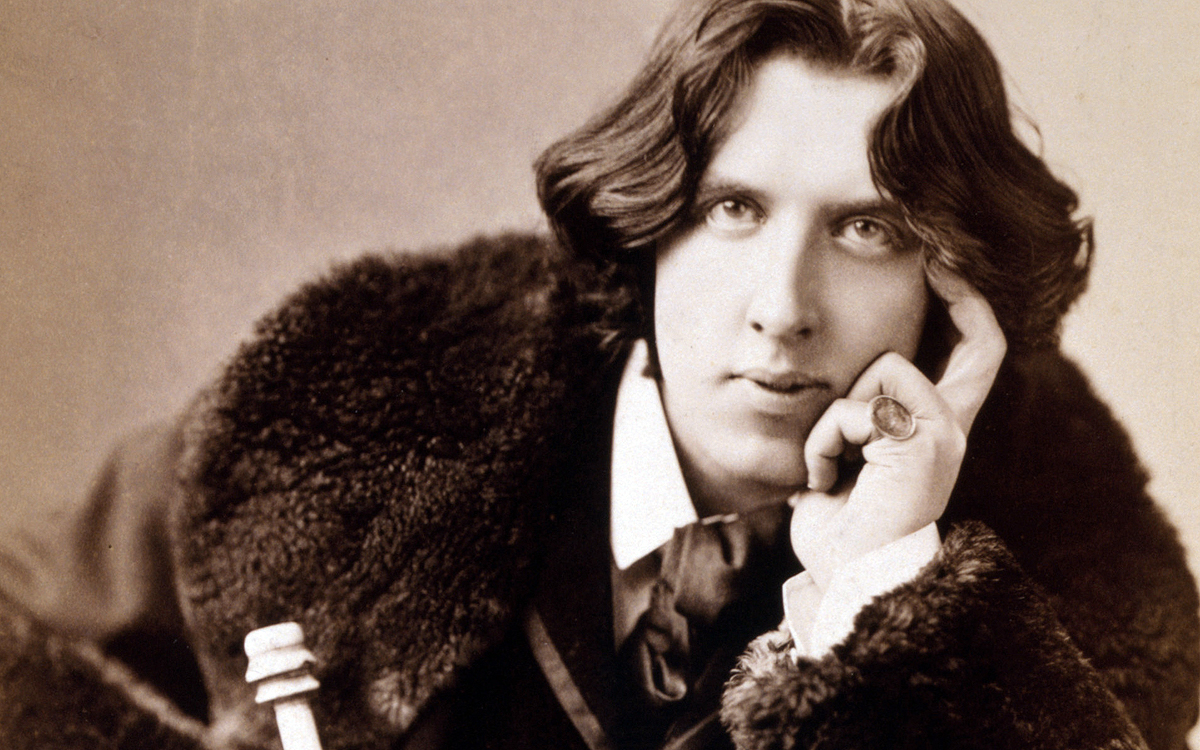

It is said that ‘life imitates art’. It is a phrase plundered from anti-mimetic thinkers, it’s provenance lying somewhere between (who else) Oscar Wilde and Aristophanes, generally, though, when people say it they’re referring to something more banal, like people reproducing exciting things they saw fake people doing on a TV show or movie: street car racing and its consequences supposedly increases by around 30% after every Fast & The Furious movie comes out.

Art, at its best, is not endless recreation of nature and natural creations, it is something that steps beyond its surroundings and gives people a glimpse at something other than what surrounds them. Any great exhibition of good or interesting ideas – note that those two categories are mutually exclusive – is capable of recreating this. The people who push the collective onwards, the over referenced and thus devalued ‘innovators’ of this world come in many different guises and industries but their importance can be summed up by one word: prescience. These ‘idea people’ show the rest what might be, what could be, what, perhaps, should be. It is only natural that people end up emulating those visions.

In the last 50 odd years of international development, the dominant ideas showmen have predominantly been economists. The grand international post war institutions like the IMF and the World Bank set a template that raised economic theorists (as well as, obviously, practitioners) to the heights of influence. They aren’t by any means the only big figures in the field but their names are most easily used as a shorthand for the approaches and thinking of institutions and organisations that lie within the uneasily confined ‘development’ box. Even in the post 80s paradigm, the rise of NGOs and a general backlash to what had gone before, the conversation remains dominated by economic thinkers – Sen, Sachs, Easterly come immediately to mind.

This setup has obvious convenience: practitioners need to be attuned to the thinking of funders, funders are likely to either be or be heavily advised by people who know a lot about money. It also has its detractors who tend to fundamentally disagree with the outlook of economics, preferring instead its sister social sciences such as anthropology or sociology. This is a debate to be had somewhere else but I will say this: the social sciences and its focus on analytical thinking are, I think, the natural epistemological fit for the industry (which is why I decided to study it) but it is limited in certain respects – anything reliant on statistics and critical thinking is likely to be. I often wish it were easier to incorporate creative thinking into the industry.

Sadly overshadowed by the vapid trappings of the much hyped Hirst exhibition at the Tate Modern in London was a show dedicated to the varied and stubbornly self determining career of the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama. In the late 1950s, about halfway through her career, she found herself in New York; a stranger in a strange land. She created a series of photos showing herself in perfect, stereotyped order – clothes, colours, makeup – but the streets around her are depicted through a distorting lens which curves the straight lines of recognisably 20th century USA roads and buildings all around her. The unreality of outside world is reflected onto the idealised version of an exotic oriental woman, an image that she inhabits for the photos.

Looking at the slide show of these images I was struck, with real clarity, that it is this exact process that is so problematic in the world of international development. The way in which charities depict themselves echoes Kusama: what the public see, even if it’s a problem, is the perfect and orderly version of the issue. You get a charity as a perfect alien, out of place and time, that willfully changes the real problems of the world around them so as to appear like an exotic, exciting, orderly being. This isn’t ever true.

“The singularity of the Guermantes who, instead of conforming to the life of society, modified it in accordance with their own habits (unworldly, so they believed, and deserving in consequence that worldliness, that thing of no value, should be humbled before them)”

Proust, Sodom & Gomorrah, p 6

Just recently I have been indulging myself with another Bit Of Art, part 4 of Marcel Proust’s epic and mind expanding In Search of Lost Time (buy this version, not the Remembrance of Things Past one). I love this book and cannot recommend it enough – I’ve gushed over it before here (page 24). Just over a week after seeing the Kusama exhibition I found myself reading the above quote, which discusses the dominant family of Proust’s work (the Guermantes) and the way in which their self regard actively changes the world around them – another example of ‘art’, meaning artifice, or human creation, being imitated by ‘life’. Again, it struck me as a window into what is wrong with the way in which the world of development treats its audience, in terms of both its donors and benefactors.

This, again, is another argument best left to another time. Again, I’ll give you a one sentence takeaway:

Creativity isn’t something that NGOs need just to improve their branding; it’s a way of thinking and interacting with the world that could lead to new and interesting angles to an industry that seems to be suffering a bit of a mid-life crisis.